Workin' in a Coal Mine

(From National Fire & Rescue Magazine, August, 2002)

Here’s a scenario for you: Imagine you respond to a report of a working fire in your neighborhood. You arrive, put on your SCBA, gather all your tools, and then report to your Chief for instructions. “You guys are the first-in search team,” he says. “We need you to go in, find the fire, and search for victims. We think we know where the fire is. Take the #3 Entry in about two miles, then at Crosscut #85 make a left….”

Two miles?! “#3 Entry”? “Crosscut #85”? What??

Welcome to your first fire at a coal mine! As you’ll see, even if you’re an experienced interior firefighter, the logistics and challenges of fighting a fire underground are like nothing you’ve ever experienced before.

~~~~

In today’s modern world, with all the concerns and publicity over nuclear power, and with steady advances being made in natural-resource power generation such as wind and solar power, it’s easy to forget that coal and coal production still plays a major part in our nation’s energy needs: in 1996 over 56% of the net electricity generated nationwide came from coal. In fact, the United States contains the largest reserves of recoverable coal in the entire world, with close to 24 million tons in deposits spread out over 38 states.

But while advances in mining

equipment and technology have enabled mines to increase coal production over

the years by a large amount, the actual number of mines has been slowly

decreasing over the years, due to increased production costs, stiff competition

and the economy. In 1980 there were 3,872 coal mines in operation in the United

States; now there are but 850 left. It is still a $20 billion-a-year business

however, with over 90,000 employees nationwide.

Along with the big numbers, though, come the hazards of what is still probably one of the most dangerous jobs in the world. Since records were first kept in 1839, close to 14,000 miners have lost their lives in over 621 disasters while working in mines. The majority of these fatalities were due to explosions within the mine, but a substantial number of deaths – over 977 – were due to fires, including the Cherry, Illinois mine fire of 1909 where 259 miners were lost. More recently, 27 miners were killed in 1984 at a mine fire at the Wilberg mine in Utah.

The issue of mine safety, including mine fires, has not been overlooked by the U.S. Government. In fact, the mining industry is perhaps the most regulated industry in the entire country. After a horrific year in 1907 where 3,242 miners perished in a single year, Congress established the Bureau of Mines in 1910. It was not until 1941, however, after 27 miners were killed in four separate explosions that the government began to take an interest specifically in mining operations. As time went on, and as more accidents occurred, the government began to increase their influence with the implementation of safety regulations and working standards. More laws were passed, each more stringent than the last, and in 1973 the government formed the Mine Enforcement and Safety Administration (MESA) as a division of the Department of the Interior, designed to carry out health and safety enforcement at mines. In 1977 the Federal Mine Safety and Health Act passed by Congress moved the enforcement agency (MESA) to be under the Department of Labor and re-named it the Mine Health and Safety Administration (MSHA, pronounced “im-sha”), as it is today.

This Act also had significant other ramifications to the mining industry: for the first time, the law created provisions for mandatory emergency training for the miners, and required at least two Mine Rescue Teams for all underground mines. The Act requires that these provisions – along with a host of other health and safety regulations – be inspected at least four times a year by Federal MSHA Inspectors. In reality, the inspectors can come at any time, and often show up for inspections much more frequently than is required.

In many ways this was good, but in some ways not good enough. Despite the improved effort on the government’s part to improve mine safety, the reality was that when it came to implementing fire prevention and suppression practices, for many years and up until very recently most mine owners, quoting poverty, did nothing but adhere to the bare minimums of the requirements of the Mine Safety Act. Any suppression equipment purchased was lowest-bid and in bare minimum quantities, and employees were “trained” in fire suppression by being told, in effect, “OK, so there’s a fire extinguisher over there - familiarize yourself with it”.

Most mine owners – but not all. Bob Murray, CEO of Murray Energy Corporation, the largest independent coal operator in North America, saw things differently. “In the four decades I have been in the business of coal mining,” he has said, “nothing worries me more than mine fires”. As head of eight different mining operations and with hundreds of millions of dollars invested in the industry, Murray realized that any human toll notwithstanding, fire would shut down a mine more quickly and easily than any cave-in, explosion or flood, and that an investment in fire training for his employees would more than offset any losses he would incur should he have a fire at one of his mines.

Murray decided to take matters into his own hands. After doing some research, he came across Bill Moser, who was already teaching fire prevention and suppression techniques to miners as an instructor with West Virginia University’s College of Engineering and Mineral Resources Extension and Outreach Program. The college had been taking advantage of a new Mine Safety Lab – which was in effect a simulated “mine” located inside a large building – that had been recently constructed on the campus of the National Mine Health and Safety Academy located in Beaver, West Virginia. The academy, a state of the art facility built in 1979 by MSHA with the aim of training both miners and MSHA employees in safe mining practices, was the perfect venue to teach miners techniques for fighting mine fires.

Murray was impressed with Moser enough that in 2001 he hired him to head up the new Emergency Preparedness division of Murray Energy. In doing so, he became the first mine operator to have his own “in-house” safety training division, and the first of a new breed of mine owners who are working to bring the mining industry up to today’s fire safety standards with both equipment and training, making their mines safer places to work.

~~~~

As a structural firefighter, I knew next to nothing about how one would fight a fire in a coal mine. So, it was with a great deal of interest then that I found myself sitting in a classroom at the Mine Academy, along with 12 employees from the Ohio Valley Coal Co. Powhatan #6 Mine in St. Clairsville, Ohio, preparing to do some “hands-on” training in the Mine Safety Lab as part of a Basic Fire Brigade class that is offered by WVU Extension.

The first part of the class was a

lecture, and it was during this time, while the miners were learning

firefighting basics, that snippets of information came through that started to

give me a chilling picture of what fighting a fire in a mine could be like.

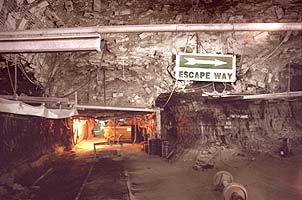

First of all, many underground mines are huge – much, much larger than people normally realize. The Ohio Valley Mine, for example, runs close to eight miles in length underground and is miles wide in some places. Mines are divided up into entries, which are like avenues, and crosscuts, which are akin to cross-streets in a city. These are created by mining out the coal in this fashion as they move in, leaving pillars of coal 75 to 90 feet square in between them to support the roof. Many mines will have several entries in parallel, resulting in a sort of “grid” layout. If you were to take a mantrip (transportation) from the portal (mine opening) or bottom of the mine (where the elevator down into the mine lets you off) inby (traveling into the mine) to the face of the mine (where the actual mining operation is taking place that day) it might take you easily 45 minutes to an hour just to get there. This fact is extremely important when it comes to considering a quick and efficient suppression of any fire that might occur up at the face of the mine: if it is not extinguished quickly, help in many cases is at least an hour in coming, and at that point it maybe already too late.

The next aspect that was brought

home to me was that coal mines contain seemingly endless sources of ignition

for a fire. In addition to methane, an odorless, colorless gas that is produced

as a by-product of coal that is extremely explosive (it has an explosive limit

of only 5% - 15%) there is coal dust, which can be explosive in and of itself.

In addition, working mines contain all of the fuel and ignition sources that

would be associated with any large industrial operation: oils, grease,

solvents, compressed gases such as propane, acetylene and oxygen, torches,

batteries, wood timbers, etc. Then there are items unique to mines: friction

from coal dust that has gathered on conveyer belt rollers, or sparks from a trolley

wire, which is a 300 volt DC cable that is strung the length of an entry in

some mines that is used to power equipment along a haulage, or railway,

in and out of the mine. Last, but not least, is the coal itself: if a fire

burns long enough and gets hot enough, any coal in the vicinity will ignite,

and when that happens…well, let’s just say you won’t be home for supper.

Other hazards to consider: PVC piping, used to carry water and electric cables through the mine, and rubber, used on tires and conveyer belts, give off Phosgene, Hydrogen Chloride and Hydrogen Cyanide gases when they burn. Add water, as if from a fire hose, and – voila’ - you have Hydrochloric Acid. On the subject of water and fire hoses, one needs to consider the amount of pressure lost from friction loss in a 4” pipe, three miles long…and did I mention that the resin glue, used to hold the roof bolts that help support the overburden (the earth above the mine) and help prevent the mine from caving in, deteriorates at 450 degrees Fahrenheit?

Then there is the issue of Ventilation, which can either be a Godsend or your Worst Nightmare in a mine. There is an entire science, and very strict MSHA regulations, dedicated to airflow within a mine. In essence, and in most cases, air is drawn (as opposed to pushed) in at the bottom of the mine, routed inby down the entries to the face, and then routed back along a different route and/or set of entries outby (away from the face) until it is sucked out of the mine by huge, powerful fans. While simple in concept, it can get very complicated, especially if there are several mining operations working at the same time in different sections of the mine that each require a specific airflow pattern. Add to the mix MSHA requirements such as the belt entry (the entry that holds the conveyer belt that removes the coal from the mine) needing to have its own separate airway, and you begin to get the idea: if a fire is in a section of the mine that you can reach from “upwind” so to speak you’re in luck; if it happens on a beltway – where due to airflow requirements the air can be flowing can be over 300 cubic feet a minute, spreading the fire down the belt (filled with coal, by the way) at 5 feet per minute, and the only way you can reach it is by coming in from outby – well, again, you can leave the dinner plate in the oven.

~~~~

On the second day of the Basic Fire Brigade class we get

treated to a hands-on “problem” in the Mine Academy’s Mine Safety Lab. A fire

is simulated by filling the entire “mine” with smoke, and the Ohio Valley crew

is asked to find the “fire” at the far end of the mine and then attack it from

three different angles using three hose lines. But our instructors Joe Spiker

and J.D.  Martin have made this far from simple: one entry has a bad “roof” in

one area, there’s been a roof fall (cave-in) that blocks another entry,

and stoppings (walls closing off crosscuts, used to direct air through a

section of the mine) prevent easy passage between the entries, so we’re forced

to use only those stoppings with man doors (a door so one can pass

through a stopping). While the

miners busied themselves with stretching hose, they seemed, despite the smoke

and being brand-new to using SCBA, to have no trouble finding their way around

the “mine” and its obstacles, while I, a supposed veteran of interior searches,

stumbled about in confusion: Every wall looks the same, every entry like a

crosscut and every crosscut an entry…and right- or left-hand leads are useless.

I was forced to admit to myself that I was hopelessly lost in the smoke and the

dark. I thought to myself, “What if this was a real fire in a real mine?”

Martin have made this far from simple: one entry has a bad “roof” in

one area, there’s been a roof fall (cave-in) that blocks another entry,

and stoppings (walls closing off crosscuts, used to direct air through a

section of the mine) prevent easy passage between the entries, so we’re forced

to use only those stoppings with man doors (a door so one can pass

through a stopping). While the

miners busied themselves with stretching hose, they seemed, despite the smoke

and being brand-new to using SCBA, to have no trouble finding their way around

the “mine” and its obstacles, while I, a supposed veteran of interior searches,

stumbled about in confusion: Every wall looks the same, every entry like a

crosscut and every crosscut an entry…and right- or left-hand leads are useless.

I was forced to admit to myself that I was hopelessly lost in the smoke and the

dark. I thought to myself, “What if this was a real fire in a real mine?”

A half hour or so later, after the team had successfully located and extinguished the “fire”, they found me and led me out. I was hoping my experience in a real mine wouldn’t be as difficult.

Fortunately, it was not. A rainy morning found me sitting in

the training room of the Ohio Valley Coal Co. Powhatan #6 Mine, attending the

required safety course that would possibly save my life in the event of an

emergency underground. After a short video on “do’s and don’ts” in the mine, it

was time to learn about our Self Contained Self Rescuer (SCSR) breathing

apparatus.

It may be

hard to believe, but it has not been until very recently – and with thanks to

the efforts of people like Bob Moser – that traditional SCBA as we firefighters

know it have been introduced into use at coal mines. There are two kinds of

SCSRs that are used instead: small emergency Carbon Dioxide filters that one

can wear on a belt until needed, and larger units – 8” square or so - that are

placed strategically throughout the mine. The smaller units are essentially

just carbon dioxide filters, with a rated use of only 15 minutes or so, and are

meant only to help you in an emergency get to a safer area and/or where the

larger SCSRs are stored. The larger units, manufactured by companies like CSE,

MSA and Ocenco, work on a sort of “re-breather” principle. Some units, such as

the Ocenco models, use a small oxygen bottle and a “scrubber” canister to

convert exhaled carbon dioxide into breathable air; other units, such as those

made by CSE, accomplish this chemically, using a potassium-super oxide mixture

that reacts with the moisture in our exhaled breath, absorbing the carbon

dioxide and producing oxygen. Both systems have a rated use of one hour, and as

none of the systems use a face mask, none are intended to be worn while

fighting fire. Until SCBA’s become common in mines, if there’s any kind of hot,

smoky fire going on it’s still going to be a rough gig.

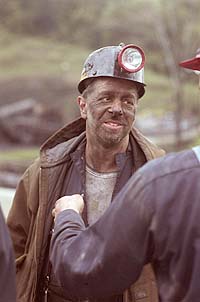

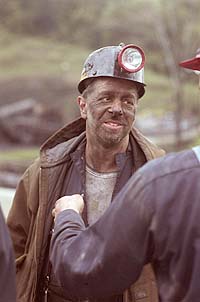

Finally it was time to visit the mine. Accompanied by West Virginia University Extension & Outreach Director Jim Dean, Ohio Valley’s Safety Director Jerry Taylor and Miner Jerry Baker, after leaving our “accountability tags” on a rack at the entrance to the mine we took the elevator to the bottom of the mine and made our way in.

The first thing I noticed, to my surprise, was that everything was white – not black, as I had expected. “That’s the rock dust,” Jerry Taylor explained. “After an area is mined, powdered limestone is sprayed on all of the surfaces of the mine as a method of fire prevention.” The limestone can also be used for fire suppression: as we continued in, I noticed bags of limestone piled at regular intervals along our route.

Our first stop was a “safety station” of sorts. Here was a rail siding that contained two low, squat rail cars, designated as a “Fire Car” and “E-Car” respectively.

The Fire

Car was a rail car designed specifically for use in mine firefighting.

Manufactured by the National Mine Service Company, it measures roughly 10’ x

20’ and carries 1,000 gallons of water. On one end of the car there are two

hose reels, each carrying 500’ of 1-1/2” attack line; at the other end is an

electrically-powered single-speed pump with two discharges. Power to the pump

is supplied by two jumper-cable-type cables with alligator clips at the ends

for attaching to a trolley wire or other DC power source. One rather cool

feature of the Fire Car is a set of retractable rubber wheels mounted along the

side of the car, which are stowed in the “up” position while the car is on

rails, but which can be lowered at anytime to move the car off into an area

with no rails if need be.

The Fire

Car was a rail car designed specifically for use in mine firefighting.

Manufactured by the National Mine Service Company, it measures roughly 10’ x

20’ and carries 1,000 gallons of water. On one end of the car there are two

hose reels, each carrying 500’ of 1-1/2” attack line; at the other end is an

electrically-powered single-speed pump with two discharges. Power to the pump

is supplied by two jumper-cable-type cables with alligator clips at the ends

for attaching to a trolley wire or other DC power source. One rather cool

feature of the Fire Car is a set of retractable rubber wheels mounted along the

side of the car, which are stowed in the “up” position while the car is on

rails, but which can be lowered at anytime to move the car off into an area

with no rails if need be.

The E-Car

staged next to the Fire Car was also very interesting. At roughly the same

size, it was essentially a mine “ambulance” that would be used to transport miners

to the bottom of the mine in the event of a serious injury. Equipped with a

built-in gurney that can be slid out from doors that open on the side of the

unit,  it carries first-aid supplies and a battery that can be used to run the

vehicle in the event of a power loss in the mine.

it carries first-aid supplies and a battery that can be used to run the

vehicle in the event of a power loss in the mine.

It was now time to visit the face of the mine where the longwall mining was taking place. We made our way to the nearest mantrip – a four foot high electrically powered train car with passenger compartments at either end - and while Jerry Baker sat up top and took the controls, Jim Dean and I half sat/half lay down in the low, cramped passenger compartment for our ride in. At first we talked, but after awhile the experience of being in the mine took over, and we switched off our headlamps and rode along in silence.

There was a peacefulness to being

in the mine. Aside from the creaking of the mantrip moving over the rails as we

bumped  along, it was utterly dark and utterly quiet. Occasionally we would stop

and a rail junction, and Jerry would walk over to a telephone hanging on the

wall and call the mine dispatcher, in order to gain clearance to move into the

next section of the mine – it wouldn’t be good to come face to face with

another vehicle coming the other way and have no place to pass or turn around.

Once, off in the distance, we saw headlamps bobbing. Greetings were called out,

laughter exchanged in the dark. We continued on.

along, it was utterly dark and utterly quiet. Occasionally we would stop

and a rail junction, and Jerry would walk over to a telephone hanging on the

wall and call the mine dispatcher, in order to gain clearance to move into the

next section of the mine – it wouldn’t be good to come face to face with

another vehicle coming the other way and have no place to pass or turn around.

Once, off in the distance, we saw headlamps bobbing. Greetings were called out,

laughter exchanged in the dark. We continued on.

And on, and on. The true size of the mine was brought home to me, as we passed row upon row upon row of crosscuts. Jim mentions to me that miners will often sleep during the trip, and as we slowly move on, I believe it.

It is fully 45 minutes later before

we reach our destination. The sound of machinery begins to grow louder, and I

see lights up ahead.  We disembark, and make our way up to where the mining

operation is taking place.

We disembark, and make our way up to where the mining

operation is taking place.

The Longwall Shearer is a

truly impressive machine, and represents the state-of-the-art in the mining

industry. When mining a panel of coal that is roughly 1,000 x 13,000 feet,

the machine works by using dual rotating drums to shear off layers of coal from

the short side of the panel by moving back and forth along a track, similar to

how a saw cuts slices from a ham when you order a sandwich at the local deli. A

fine spray of water is used as well, to cut down on the amount of coal dust and

help minimize any explosion hazard. The coal is then carried parallel to the

miner on a conveyer belt out to the headgate, where it meets up with the

main beltway to be carried out of the mine.

Behind (and also parallel to) the shearer is a line of 200 or so 5’wide steel hydraulic shields, which support the roof above where the mining is taking place, and which are designed to be moved forward individually as the shearer moves past, ensuring safe operation as they move along. Behind the shields, in an area called the gob, the roof is allowed to cave in – after the mining has been completed.

This sounds safe in theory, but it was no comfort to me, as while moving past the headgate, ducking to avoid hitting my head on the headgate shield while slipping in coal mud in the dark, a large chunk of roof behind the shield suddenly caved in to my left with a large crash, causing me to suddenly hop-to-it on out of there. I was told this was normal, but the look on my face gave the miners there quite a chuckle.

~~~~

Three days later I was again risking my life in the name of

journalism, at the PennAmerican Burrell Mine in Blairsville, Pennsylvania. It

was an important day for the mine: today the first group of employees would be

getting their first hands-on training in fire safety and suppression. Bill

Moser was on hand with a pile of fire extinguishers and a brand-new,

one-of-a-kind Mobile Training Unit. Essentially a maze-on-wheels, the Mobile

Training Unit is a 2002 Freightliner Model FL60 with a custom box that contains

a three-tiered gallery that is divided up into wire mesh “tunnels” 30” square,

so that when darkened and filled with smoke it becomes a confined space

three-level maze that mine workers must find their way through, simulating

conditions that would be encountered in a mine fire.

As Moser took turns with each of the miners, showing them fire extinguisher operation basics and timing them through the maze, I was introduced to Dan Couch, General Manager of the Burrell Mine, and Bill Kokla, the Safety Director. Bill equipped me for a tour into the mine to witness a continuous mining operation – using a machine with a large rotating steel drum with tungsten carbide teeth that is used to scrape coal from the seam.

On the long ride in to the face my thoughts again wandered, and it made me shudder: Unlike the Ohio Valley mine, where we could for the most part stand up, the Burrell Mine has a coal seam only 48” high, necessitating a sort of duck-walk-crawl wherever you go. How would one navigate into a fire in this space? If there was a fire four miles in and there was no mantrip available, it would take you two and a half hours on your hands and knees…and the average age of the mining workforce is close to 50 years old. We firefighters are used to interior conditions at a fire, but miners – and even mine rescue teams – may only see one or two fires in their entire careers…will they be trained enough and ready if – God forbid – that day ever comes?

At least, with the efforts of men like Bob Moser, and the WVU Extension Program, and the Mine Academy’s Mine Safety Lab, there is hope.